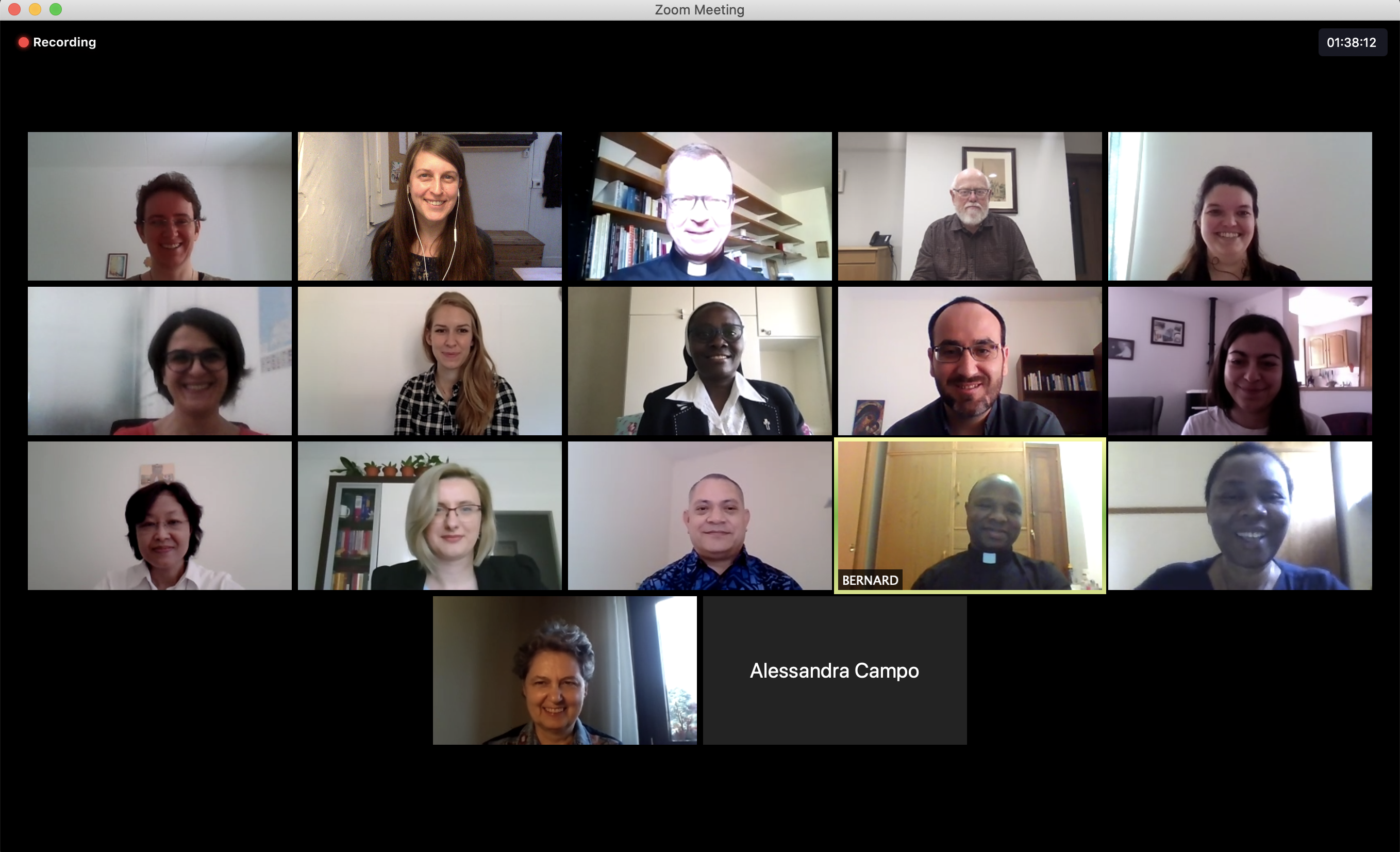

Remote commencement exercises for first graduating licentiate class

On June 12, 2020, the Centre for Child Protection held commencement exercises for seven licentiate students via Zoom. The seven graduates are Sr. Jane Nway Nway Ei, Fr. Pedro García Casas, Fr. Bernard Malasi, Sr. Theresa Olaniyan, Sr. Barinem Bernadine Pemi, Ms. Marina Šijaković, and Fr. Sione Hemaloto Simeti Vave.

A keynote was given by Ger Crowley, Director of Safeguarding Children for the Limerick Diocese in Ireland. His address included five things he has learned over the years regarding the role of a professional tasked with safeguarding:

- Don’t assume people in positions of responsibility and authority can always be trusted.

- Have a healthy suspicion of your own capacity to evaluate situations.

- At an organizational level don’t be a vain hero. Share the responsibility.

- What’s not written doesn’t exist!

- It is important to mind yourself.

His discussion of these points was forthright and his gentle style of communication came across well, notwithstanding the challenges of a remote audience. We share the video here at the request of the staff and students who appreciated his insights very much.

The Centre for Child Protection wishes the best to its new graduates and gives heartfelt thanks to all who made it possible!

https://youtu.be/wtfVZpplv4E

The full text of the keynote is provided below with permission of Ger Crowley.

Gregorian Lecture June 2020

Introduction

Thank you for inviting me to be with you on this very special day as you leave the Gregorian and move on to the next phase of your lives. I would like to wish warmest congratulations to you all. You will understand me congratulating Sr. Jane in a very special way as she spent a number of months with us in the Diocese of Limerick in Ireland and that was a very special time for all of us.

I am sure that you have learnt a great deal from the learned and wise people at the Gregorian. As you look towards your future life in safeguarding my few words are not based primarily on research or academic learning but rather on the mistakes of over 40 years’ involvement in safeguarding and a little of the lessons learned, which I hope will be of some help to you.

Learning from Mistakes

Over 40 years ago I graduated from two universities and worked as a social worker and as a manager of social work services without ever hearing the term child sexual abuse. This led to 20 years in practice during which I did not understand what many children and other vulnerable people were experiencing and, therefore, working from mistaken beliefs. This inevitably led to poor professional practice.

Changes in our society and most importantly the courage of mainly women in breaking down the shame barrier which had prevented them from speaking, and I and my peers from hearing, meant that much of the next 20 years has been spent trying to deal with the fall-out of historical failures.

So my few words to you this morning are based on a lifetime of mistakes and of struggling to address these mistakes.

I suggest that my mistakes are not just of historical interest as there is always a danger in dealing with something as complex and emotive as safeguarding that we may repeat the same mistakes, particularly if we don’t reflect on them and learn from them.

What is clear is that abuse has at its core the combination of power and powerlessness. Relative power is an element in all relationships. However, when the gap in relationships between power and powerlessness is great, danger lurks.

It is not accidental that vulnerable people are at greater risk of abuse. Children, older people, people with disability, people with mental health issues and people who are separated are at risk of being abused by those who have power over them.

In the context of the Catholic Church, this is equally true even when that power is designed and meant to be about caring for these vulnerable people. This corruption of care, coming from the dark side of human nature, facilitated by the gap between power and powerlessness and our tendency not to face this, can be the foundation for our mistakes.

I want now to share five points of what I’ve learned

- Don’t assume people in positions of responsibility and authority can always be trusted.

The first really significant mistake I made was making an assumption that people in power, in positions of responsibility and particularly those in caring roles, could be trusted fully. This was a dangerous assumption.

To this day I remember the first children, three members of the same family, that I brought into the care of a residential care service funded by the state and operated by a religious congregation. I remember that afternoon, over 40 years ago, and feeling so relieved and glad these children were now safe. Many years later I had to meet these three children. They had all been abused while in the safe care where I had placed them.

I had presumed I could trust that religious congregation where I knew there were many fine people.

You will recall that the assembly of church leaders, called by Pope Francis in 2019, included themes of accountability and transparency. It is wiser to always assume that relationships and services that have the combination of power and powerlessness are inherently potentially dangerous.

Systems and practices must be developed to ensure that all such relationships and services are open to scrutiny and accountability which is independent of those in positions of power.

Trust is of course necessary in all relationships, but in this context, the trust must be matched with clear verification.

This, in my experience, is true at a personal level and at an organizational level.

- Have a healthy suspicion of your own capacity to evaluate situations.

All of us make mistakes…. all of us get it wrong.

My biggest mistakes flow from a tendency, which many of us share. That is a tendency to believe in my own capacity for insight and good judgment and in the rationality of my behavior.

Safeguarding is not an exact science but rather is deeply subjective. So for example we see that significant issues about the very definition of child sexual abuse still exist. So also do the diversity of views and legislation on capacity to consent.

In this context, if we hold on to an unwarranted sense of our own capacity, we are confronted by abusers who distort and manipulate and draw everyone into their distortions. Therefore, when I try to do this work alone I damage not only the people I serve but also myself. My emotions and angers become displaced and my thinking becomes self-serving.

I have had to accept the anger that I feel towards the men I work with who have abused and my only choice is how I deal with this anger.

I find it harder to accept that I feel angry at times with people who have been abused when, for example, they turn their pain and anger on me and are critical of my response.

You will have learned from the research on the impact of child sexual abuse of how the experience of abuse can alter the person’s cognitive and emotional orientation in the world. It is, however, one thing to read of the impact on a person’s capacity to trust and the effect of feelings of stigmatization and powerlessness, but it is a very different experience when these dynamics are played out in your relationship with a person who is very critical of you and your organization's response.

So what I’ve learned is to be careful… without support, without supervision which allows us to reflect on what we are experiencing and feeling and without collaborating with others we cannot mind ourselves and do good work. No matter how hard we work we will not be safe.

It is particularly important that we recognize and acknowledge the power and balance which can exist in our relationships with people who have been abused and have experienced powerlessness in the most extreme manner when they could not stop the violation of abuse. Failure to recognize and acknowledge this may lead to compounding the harm which people have experienced.

- At an organizational level, don’t be a vain hero. Share the responsibility.

As you return to your counties, your congregations, and your dioceses, your leaders may see you as the expert and as the solution. We all like to be valued, it nourishes us, but again be very careful. Vanity is dangerous.

We know that it is rare for organizations and leadership teams to proactively address safeguarding, more often action is taken in response to public scandal and failure. What Pope Francis has referred to as “tragic experience.” People in leadership are human with all the frailty that this brings and all too often are busy people living lives under pressure.

People in leadership will have experience perhaps of

- being abused

- being involved in situations which they do not want exposed or addressed

- perhaps are aware of how they mishandled historical situations

For a whole variety of reasons your leaders and members of your community will have feelings about safeguarding and these will create dynamics in your relationship with them.

At one level we are conscious of the pervasiveness of abuse across cultures. However, in reality, the true scale is still not evident. We can see, for example, that the results of studies that rely on retrospective self-reporting show much greater rates of child abuse than that which is evident from “official” statistics.

The available research tells us that the experience of abuse impacts very many groups and organizations and there is no reason to believe religious groups are immune to this.

As you return to your communities and take on responsibilities, it is vital that you engage in a process with your leader and leadership team.

- At the core, this must be about shared ownership of the task of safeguarding within your organizations or community’s particular context.

- It must be about agreeing on clear and realistic goals and the supports that will be in place to achieve these.

- It must acknowledge that there will be disagreements and tensions particularly with colleagues and there must be agreement in advance on how these will be addressed.

- This process must be explicit, written down with agreed review arrangements.

The greater the resistance to this process from the leader and leadership team, the greater is the need for the process.

I have, in younger days, taken the alternative heroic approach. Let me say to you with absolute certainty that if you see yourself alone as the solution, you will be seen in the short term perhaps as the solution but sooner or later you will become the problem.

Safeguarding is hard and difficult. You can be a resource to your community but you cannot alone own the responsibility.

Spending time to achieve shared ownership is time well spent.

- What’s not written doesn’t exist!

I mentioned the need for your agreement with your leadership team to be written down. If there was one practice that I would urge you to cultivate it is that of writing and recording every day. If something is not written down and agreed, then you should assume it did not happen. Certainly in controversial circumstances one's memory will not be accepted without a clear written record.

I spend a significant amount of my time looking at historical situations and reading historical files and there are some patterns that I now come to expect. One is that I will find that I am very often the first person who has read the file fully and reflected on it. In my own diocese, I have made it a practice to read our main active files every year and that discipline has taught me about how I can miss things and forget things and how that leads to poor practice and to ‘drift’ in managing issues.

What is equally evident is the pattern whereby people will have very different memories of the same incidents and the same communication. So the whispered concern shared briefly in confidence which will have included statements such as “I’m not really saying that he is doing anything… I’m just a little uneasy” may, 20 years later, be presented as “I told her explicitly and she did nothing.”

Very many times adults have told me that as children they told adults that for example “he was at me.” Both the child and the adult may agree on the words that were spoken, but their understanding of what was communicated will be entirely different.

Everything in safeguarding needs to be recorded/written and the record needs to be agreed upon by all the people involved at the time.

I am continuously surprised at my own misunderstandings when working through the record of my engagement with people, particularly when people are in pain and the subject is difficult.

We must also accept that accounts and feelings change over time.

- It is important to mind yourself.

I do not mean to frighten you or to depress you. I think the base from which you are approaching your work in safeguarding is a very different base from that of my generation.

All I am really saying is that we must assume that people who are powerless are vulnerable to abuse and that evil can coexist with apparent goodness and even nobility in the one person.

Our practice and organizational arrangements must work on these assumptions. Safeguarding brings us face to face, as you know, with the dark side of our human nature and therefore you must actively mind yourselves.

A major part of minding yourself involves having a clear relationship and understanding with those who have leadership responsibility within your congregations and dioceses.

Equally important is your support network.

People who have been abused have a right to expect that we do everything humanly possible to understand and respond as thoughtfully as possible to the complexity of their experience.

The context of your work must enable you to be grounded, to have a solid foundation if you are to do this difficult work.

Conclusion

There are fewer things in life as meaningful or as fitting for a Christian to be involved with as walking alongside people who are powerless and vulnerable and have been abused and working to keep people safe. It is a ministry in itself.

At the summit called by Pope Francis in 2019, Cardinal Tagle said,

“the Christian faith itself and the ability of the Catholic Church to proclaim the gospel is what is at stake in this moment of crisis brought about by the abuse of children and our poor handling of these crimes.”

Pope Francis has said that this evil strikes at the very heart of the mission of the Church.

Could your work, therefore, be any more important?

I would like to thank you for the decisions you have made that have led you to the Gregorian and that will lead you on to working and walking alongside the most vulnerable people in our societies.

Let us remember each other every day in our prayers.

Ger Crowley

June 2020